You're So Pretty... for a Black Girl.

☕️Deep Brew | I Spent Years Playing the Part—Now I’m Finally Stepping Into Myself

Disclaimer:

I really struggled to write this week’s article. I’ve been stuck on questions of masking, double consciousness, identity, gender, sexuality—where we, as humans, belong. All the things. I rewrote the intro at least 15 times, mindlessly daydreaming about how to encompass all the layers of a person’s identity in 1,500 words or less. Should I talk about weight loss and body size? Should I talk about beauty? Or maybe Black women’s hair, in commemoration of the 10th anniversary of Annalise Keating—a fictional Black woman attorney in ABC’s How to Get Away With Murder—taking off her wig for the first time on national TV.

Instead, I decided to write this. I know these thoughts are incomplete—just a small glimpse into one brief line of my story. But they are mine.

So, this is my story—part one, chapter one: The Beauty Queen.

The Masks We Wear

“You’re so pretty, for a Black girl.”

“Don’t stay outside too long, you’ll get too dark.”

“You don’t have that good hair.”

“Can you make your nose a little smaller?”

“Yes, sometimes they crown Black women, I think.”

They say beauty is in the eye of the beholder. But for Black women, beauty is never just seen—it’s measured, dissected, controlled.

Beauty is big business. And for most people, presenting yourself in a way that makes others feel comfortable is just social navigation. It’s a reflex, this thing we do to avoid ruffling feathers. We smooth our hair in the morning. Put on slacks one step at a time. But for many people like me—Black women—it’s not just a performance. It’s survival.

I was often the only Black girl in my primary school classes, the daughter of immigrants navigating spaces where my name, my skin, and my story were never reflected back at me. I’ll never forget being cast as a Native American in our elementary school’s Thanksgiving Day celebration, likely because of my brown complexion, or discovering I was the only kid with parents who were still classified as ‘aliens’ during a class discussion about immigration in fourth grade. (Seriously, there is nothing more terrifying to a young person than believing your parents are from outer space.)

I’ve walked into boardrooms as the youngest person in the room, the only woman of color, the only Black woman. And yes, I’ve stood on stage as the Black Beauty Queen, competing in pageants designed around ideals of beauty that never included women like me. In fact, Black women weren’t allowed to compete in Miss America until 1970, and it wasn’t until September 1983 that Vanessa Williams became the first Black woman to win the crown—more than 60 years after the pageant’s founding in 1921.

In each of these spaces, I’ve learned how to adjust—how to be what the room needed me to be. A version of acceptable Blackness.

It’s an old dance, one that many Black women have been performing for generations. And like others, I’ve become a master of it. In fact, I have the crowns to prove it.

Because when you’re a woman in America, but especially a Black woman, your body is never really your own. From the moment you take your first breath, the world starts telling you what you can and can’t be. Your body becomes something the world claims, judges, and is always policing and critiquing.

For Black women, you either learn to make yourself fit into the mold they’ve made for you, or you fight like hell to resist it. But that resistance comes at a cost.

The Beauty Standard

If you don’t fit the old stereotypes of Jezebel, Mammy, or Sapphire, you get left with one other box: the token. I know that one well. The token Black girl. She’s Lisa Turtle from Saved by the Bell, Dionne from Clueless, and Whitney from A Different World. The one who can be present, but only if she’s polished, graceful, and non-threatening. The one who fits neatly into white spaces without making anyone uncomfortable.

Being the token means you’re hyper-aware of how you’re perceived at all times. You learn early that you’re often seen, but not really seen. Your job is to anticipate the discomfort of others and soothe it—without them ever knowing that’s what you’re doing.

And even now, as I write this, I hear a small voice whispering in the back of my mind: “Is this too Black? Can I talk about this? What will my mostly white suburban readers think?”

The rules are simple but relentless:

Be visible, but not too visible.

Be vocal, but not loud.

Be confident, but never intimidating.

Be pretty, but only for a Black girl.

These are the unspoken rules, and if you’re Black and a woman, you learn them early. You carry them like armor, and after a while, you forget if the weight is protecting you or slowly suffocating you.

The Cost of Beauty

Pageants taught me how to perfect this mask. It wasn’t just about looking good—it was about projecting a version of myself that felt safe to everyone else. I had to be graceful, composed, and always smiling. (In fact, I learned to smile through yawns—because looking human wasn’t part of the job description.) I mastered how to give the perfect answer without ever seeming too opinionated and learned how to quickly make everyone around me feel at ease.

This mask has opened doors for me that my parents could never have imagined. And, by all accounts, I’ve mastered the game. But at what cost?

Recently, a friend invited me to a community event, and without realizing it, anxiety crept in. I could feel the familiar tightening in my chest. My breath coming shorter. My mind already playing the game—Who would I be this time? The polished CEO? The pageant queen with the poised smile? The mother whose hair stays in place? What role would I play there? Could I safely “let my hair down” and just be? The fact that I ran through these scenarios in my mind is why I’m writing this today.

No one should have to ask these questions. No woman should have to mentally tick off a survival checklist just to exist in a room.

When you spend your life contorting yourself to fit into spaces—becoming the “right kind” of Black woman, the “right kind” of leader, the “right kind” of anything—you start to lose touch with yourself. The lines blur between the person you are and the one you’re forced to be.

The Mask We Wear

I think about Paul Laurence Dunbar’s poem “We Wear the Mask” often. If you haven’t read it, here’s the full text:

We wear the mask that grins and lies,

It hides our cheeks and shades our eyes,—

This debt we pay to human guile;

With torn and bleeding hearts we smile,

And mouth with myriad subtleties.

Why should the world be over-wise,

In counting all our tears and sighs?

Nay, let them only see us, while

We wear the mask.

We smile, but, O great Christ, our cries

To thee from tortured souls arise.

We sing, but oh the clay is vile

Beneath our feet, and long the mile;

But let the world dream otherwise,

We wear the mask!“We wear the mask that grins and lies.” Dunbar captured it perfectly—the tension between the smiling face we show the world and the weight we carry inside. We smile, but underneath? There’s an aching. A history. A set of expectations and pain that no one ever sees.

So, is the mask a lie, or is it a necessary tool for those of us who have always lived on the outside, looking in?

Let me be clear: what I’m talking about—and what Dunbar so eloquently wrote about in 1895—goes far beyond walking into a PTA meeting and turning on the charm for the cool mom clique. It’s deeper than that. For people like me—Black women, immigrants, queer folks, anyone who doesn’t fit the mold—masking is a matter of survival.

The world wasn’t built with us in mind, so we navigate it by becoming fluent in the languages of whiteness, straightness, conformity. We learn to soften ourselves, hide our edges, downplay our differences just to stay safe.

It’s akin to what W.E.B. Du Bois called double consciousness in The Strivings of the Negro People—the constant tension of seeing yourself through the eyes of others, always measuring yourself against a standard that was never designed for you. It’s living in two realities at once: the person you know yourself to be and the version you present to be acceptable to others.

But there’s a toll to this. For every moment I’ve spent making myself more palatable, there have been three moments of shrinking. Three moments of quiet erasure. Of pushing down the parts of me that deserve to take up space but aren’t welcome in certain rooms.

The Cost of Masking

Masking didn’t just take my voice—it took my body. I’ve spent years measuring my worth in inches. The size of my thighs, the width of my hips, the space I dared to take up. Every morning, like clockwork, I’d wrap a measuring tape around my waist—tight, tighter—willing myself to shrink.

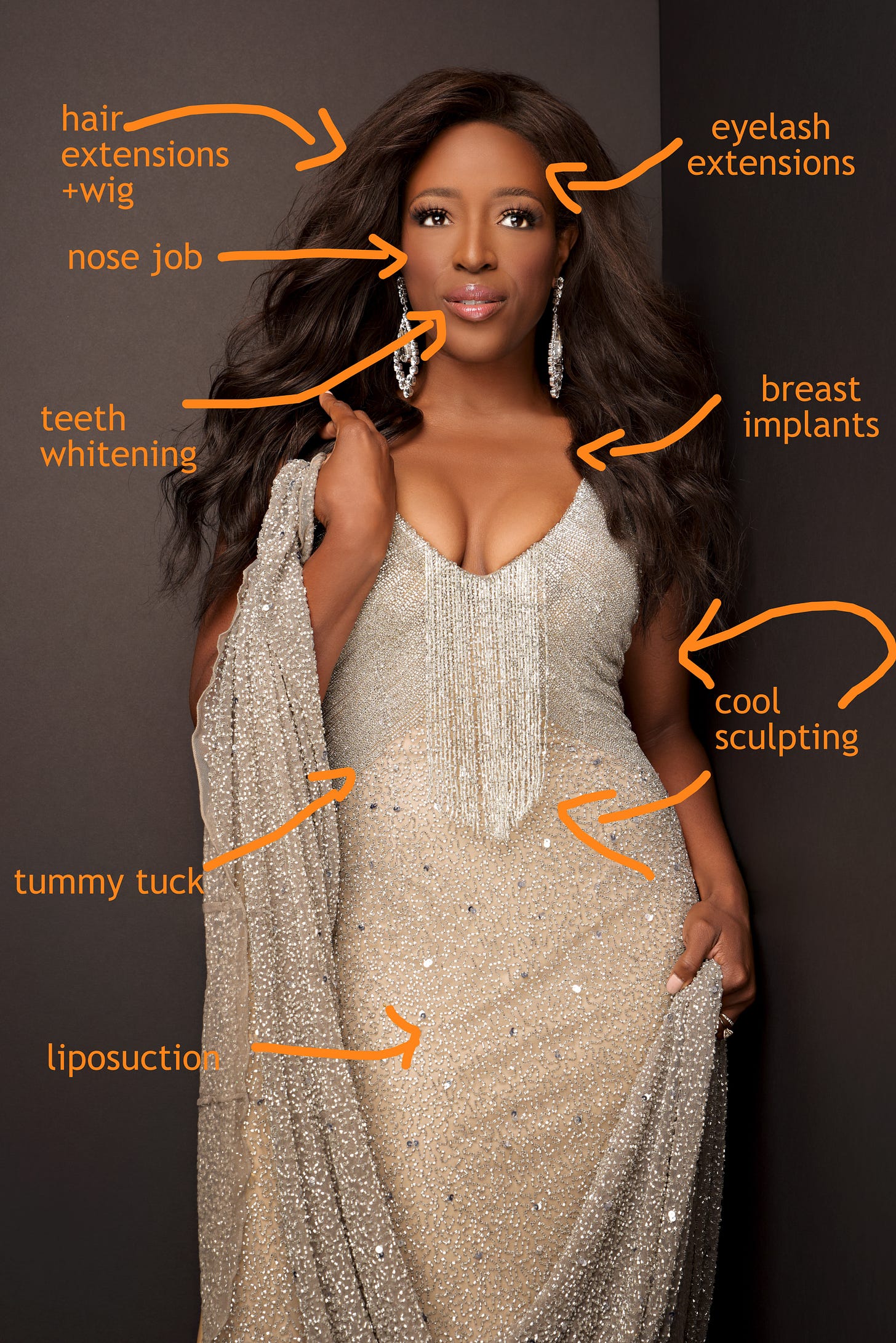

Body dysmorphia. It's such a clinical term, but for me, it’s waking up every day and seeing something distorted in the mirror. A body that’s too much. A body that takes up space it’s not supposed to. I’ve battled eating disorders for years, cycling through extreme diets, fasting, even surgeries—anything that could make me smaller, more palatable. It’s a war I still fight.

The worst part is that the world validates my insanity. Miss Mansfield, Miss Miami Valley, Mrs. Ohio, Ms. Black and Gold… a rhinestone charm to add to my collection. “You’re so pretty—for a Black girl.” Backhanded compliments, thinly veiled judgments, and I took them all as validation. I internalized those messages so deeply that my body became an enemy. I didn’t just want to shrink; I needed to. I needed to fit, to belong, to be seen as beautiful, and I believed that meant being small, being quiet, being less.

For fifteen years, I hid behind wigs and weaves, straightening my natural curls into submission because I thought—no, because the world confirmed—it was the only way I could be seen as professional, as put-together. I spent years straightening, covering, masking my hair—because even my hair was too much. And when that still wasn’t enough, I turned to surgeons, carving my body into something closer to what the world deemed... acceptable.

And then there was my voice. The way my Caribbean family speaks—full, elevated, words overlapping with hands, movement, and rhythm. I learned to suppress that, too. I was taught to lower my voice, to be softer, more agreeable, to never make anyone uncomfortable. My body, my voice, my presence—I made them all smaller. I learned to be the “right kind” of Black woman. Polished, graceful, non-threatening. The kind that didn’t make waves.

But the cost of living this way? The constant shrinking, the constant war with my own body, my own reflection—it’s heavy. It’s the kind of chain that weighs on your soul. You start to lose sight of where the mask ends and where you begin. Every suppressed feeling, every word I swallowed down, bellied up inside me like a storm, threatening to burst.

And then the mask, like a dam, cracked.

Reclaiming Power and Space

When a dam cracks, the waters don’t just flow—they carve out new paths, reshaping everything in their wake. That’s what unmasking feels like—slow, deliberate, but undeniable. A power that’s been contained for too long, breaking free. Not in a rush to roar, but in a steady, quiet force that knows exactly where it’s going—unlearning, piece by piece, how we made ourselves smaller and quieter.

So how does this connect to civic wellness?

Well, the external work of civic wellness— showing up for your community, advocating for change—is important. But none of it can be fully realized without first doing the internal work. Learning to take up space in your own skin, to feel confident in your own worth.

For years, I thought power came from fitting in, from mastering the language of those who already had it. I believed I needed permission to exist fully. But I’ve learned that the most revolutionary act is simply being—showing up as myself, unapologetically. And let me tell you, it’s hard. Unmasking is messy, uncomfortable, even painful. But it’s necessary.

This isn’t about suddenly reclaiming power and shouting, “Hear me roar!” It’s about carving out space for myself and others who’ve been on the outside looking in. Chipping away at expectations, standards, masks, and understanding that internal work is as crucial as external action.

Civic wellness isn’t just about showing up for your community; it’s about showing up for yourself. It’s about connecting with your identity and sense of purpose, knowing that self-acceptance is a form of activism. When we’re grounded in who we are, we can serve our communities with greater empathy, resilience, and authenticity.

So here’s my call to action. Maybe you’re a Black woman like me. Maybe you’re part of the queer community, or you’ve spent years trying to fit into a space that was never designed for you. Whoever you are, let this be your crack in the dam. Let this be the beginning of your unmasking, of letting the waters rush through. You don’t have to tear down the whole structure at once. But start somewhere. Start by peeling back one layer, one piece of armor, and allowing yourself to finally breathe without it.

About Coffee & Lemonade

If you want to keep up with more real talk about identity, civic wellness, and everything in between, subscribe to Coffee & Lemonade. It’s where I share personal stories, reflections, and insights that (hopefully) make you think, and push us all to do better.

Sophia, I want to squeeze you so tight right now. Thank you for sharing such a vulnerable TRUTH with us. I shared this with our Freedom a la Cart team. I know your story will impact sooo many others. Grateful to know you. Looking forward to learning more from you.

Beautifully written Sophia. Thank you for your courage and being willing to boldy share your truth in a way that empowers us all.